http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/reviews/lu-yang-/

http://www.artinamericamagazine.com/reviews/lu-yang-/

Lu Yang

NEW YORK,

at Wallplay and Ventana244

by Christopher Phillips

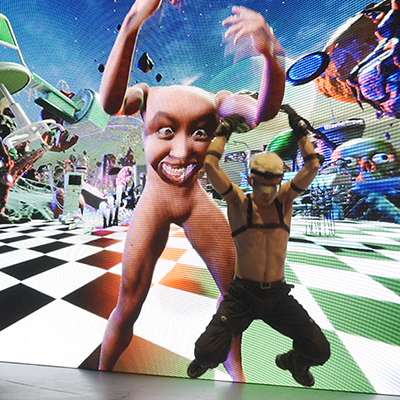

This two-gallery exhibition offered U.S. viewers their first substantial glimpse of the world of Lu Yang, the prodigiously talented enfant terrible of the Chinese art scene. Utilizing a wild mix of imagery drawn from Japanese manga and anime, online gaming culture, sci-fi, neuroscience and religion, she asks what it means to be human in the 21st century. The results—which take the form of 3-D animations, video games, augmented-reality sculptures, prints, drawings and 3D-printed objects—are fascinating but definitely not for the squeamish. Lu Yang’s work, in fact, contains something to alarm almost everyone.

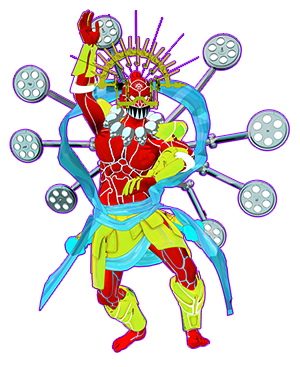

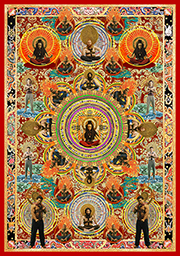

While Ventana244 showed a selection of the artist’s videos, Wallplay presented “Arcade,” a densely installed overview of Lu Yang’s projects of the past four years, since she completed her studies at the China Academy of Art in Hangzhou. Wrathful King Kong Core(2014) takes as its subject one of the “wrathful deities” of Tibetan Buddhism. His surly temper and tendency to violence are analyzed in meticulous drawings resembling medical illustrations that map the neural pathways of anger. These musings about the anatomy of rage come joltingly to life in a tabletop installation. When the viewer points an augmented reality-enabled iPad toward an empty ornamental wooden platform on the table, a 3-D animated version of the fearsome god appears on the iPad screen atop the platform and gestures menacingly at the viewer. This work, the artist says, is a way of beginning to understand the sources of human anger, obsessions and hatred.

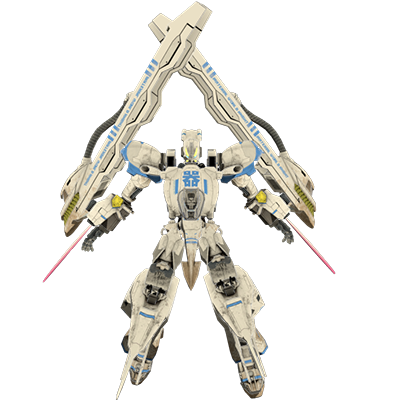

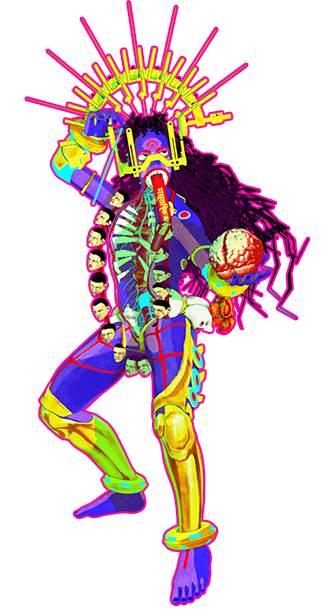

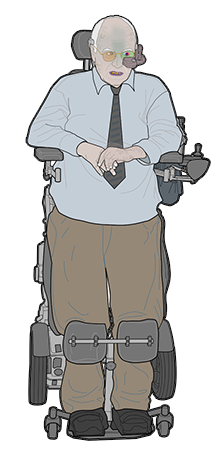

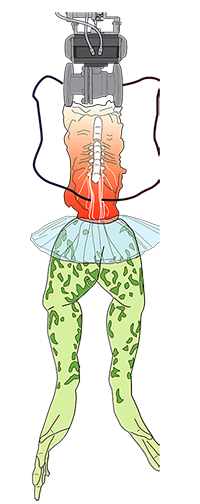

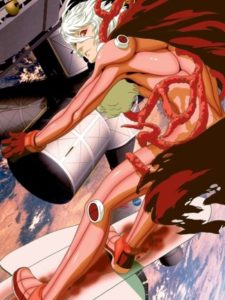

Much of “Arcade” was given over to works tracing the adventures of Uterusman, an androgynous, silver-tressed superhero whose weapons and powers derive from parts of the female reproductive system. Uterusman rides in a high-tech Pelvic Chariot modeled on the female pelvic bone. He is protected by a Placenta Defense Shield and battles his adversaries with an Umbilical Cord Whip and a ferocious toddler described as a “baby-weapon.” His powers include the ability to alter the DNA code of his enemies so as to weaken them—an eerie premonition of techno—warfare that extends to the genetic level. Noting that many visitors recoil at the sight of Uterusman’s viscera-colored costume, Lu Yang matter-of-factly observes, “People think that flesh and blood are disgusting, but we are made of this stuff.”

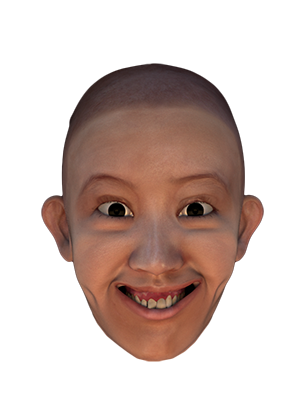

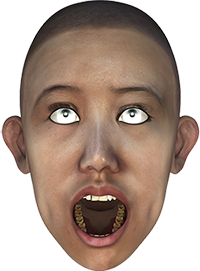

The most recent series of works shown here, “Cancer Baby,” is the most genuinely disturbing. Working with laboratory scientists to obtain microscopic photographs of human cancer cells, Lu Yang used the cells’ forms to design a group of smiley-faced cartoon characters who sing and dance their way through a kiddie-pop animation. “We are baby cancer cells,” they chirp, “We live inside your body, we grow up very fast.” Companion works included creepy-cute Cancer Baby posters (“Please Don’t Kill Us!”) and a large display case filled with 3D-printed, hand-painted Cancer Baby jewelry. In China, where toxic pollution has sent cancer rates soaring, the “Cancer Baby” series has raised hackles for its supposed insensitivity. Yet Lu Yang insists these works are meant to be cathartic, and to put a nonthreatening face on a subject that usually remains taboo. “Disease and death are part of everyone’s experience,” she has said. “You can’t get any more natural than that.” This bracing lack of sentimentality about the human condition, combined with her nonstop visual inventiveness, makes her an artist to watch.