http://www.method-magazine.com/art/2016/2/8/on-we-chat-uterusman-1

Words: Benjamin Velaise ’18

Documenting an era in which China was just beginning to open its doors to western influences, Wesleyan Zhilka Galley’s “WE CHAT” exhibition pulls from Communist iconography and propaganda to underscore the political climate of the time– juxtaposing past conditions with the present.

“WE CHAT”—playing on China’s dominant social media and messenger app that combines Facebook, Instagram and Twitter—engages artists in a dialog surrounding notions of nationality and personal identity. As such, the exhibition seeks to reflect on and contribute to a discussion surrounding not only anew Chinese identity, but the ephemerality attached to these identities as well. As curator Barbara Pollack describes, the works explore modalities of self-expression “less rooted in nationalism and cultural restrictions, one more open to global influences and transcultural participation.”

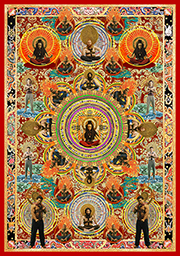

Chinese contemporary artists such as Lu Yang, Ma Qiusha, Pixy Yikun Liao, or Sun Xun engage their identities in their art, reflecting on the recent transitory nature and changes in identity that have taken place in recent years. Greatly influenced by the Communist era, notably the Cultural Revolutions of the 50’s, 60’s and 70’s, the artists’ works respond to the confusing and disturbing conditions that marked the revolutions.

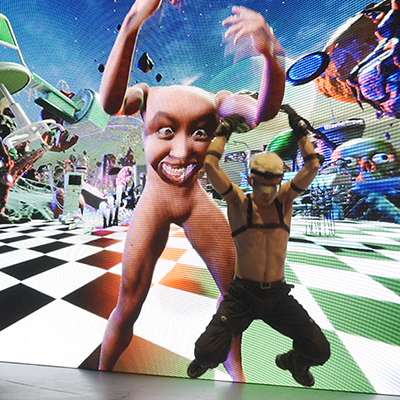

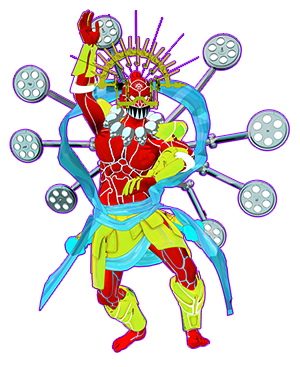

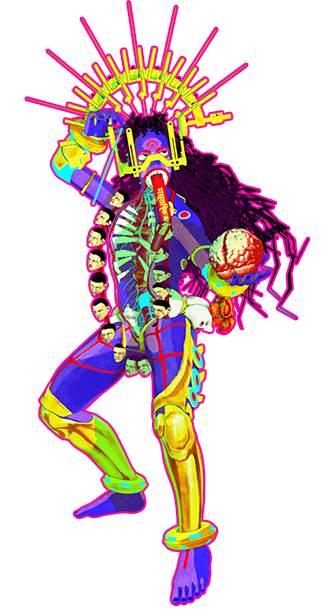

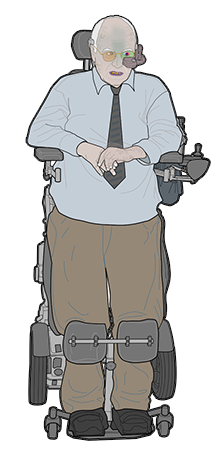

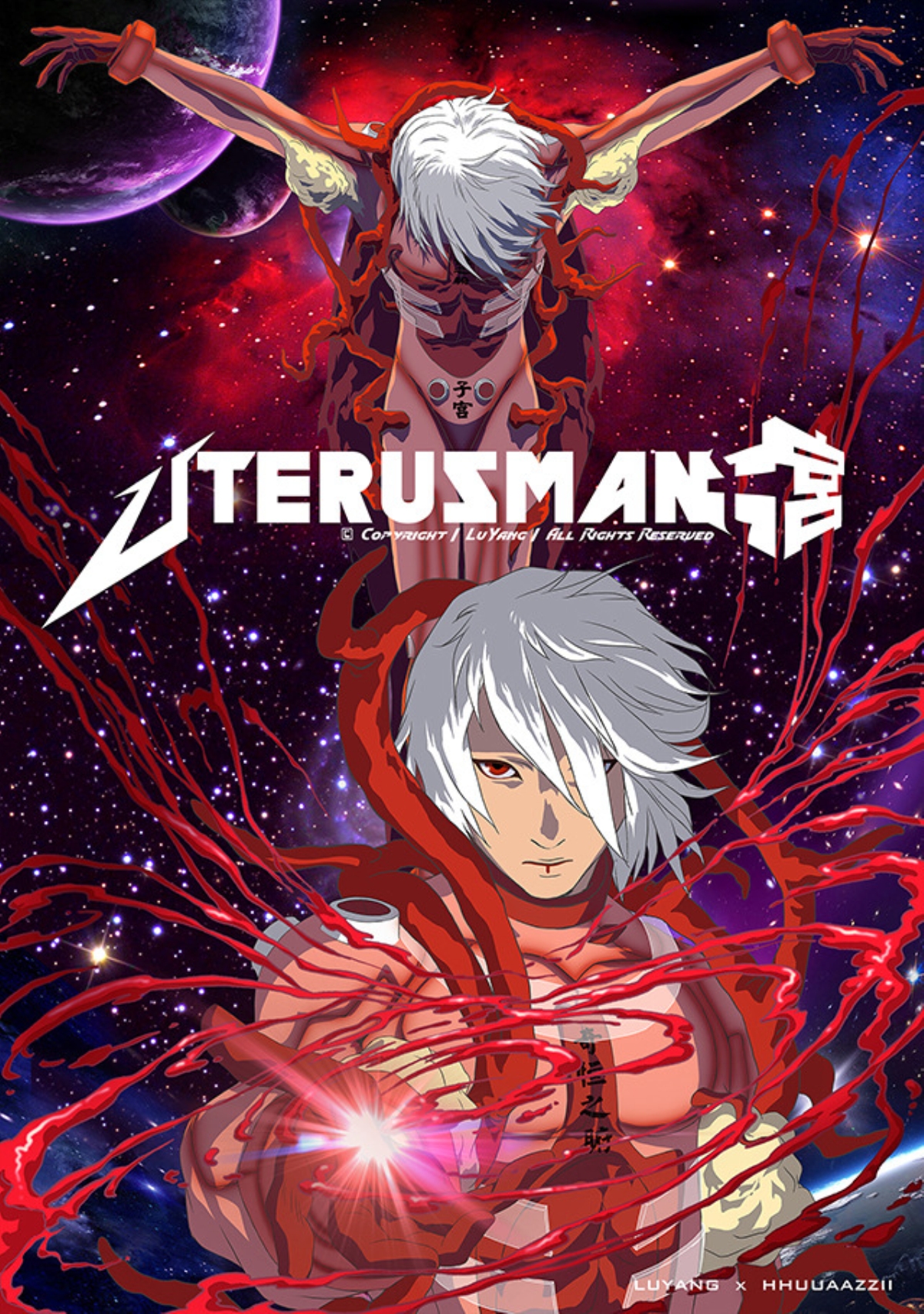

Occupying an entire hall directly en-face to the gallery’s entrance, Lu Yang’sUterusMan dominates the expedition. Projected fifteen feet high onto the concrete slabs of Zhilka, a digitally animated video plays on loop accompanied by an upbeat, video-game-esque soundtrack.

Working out of Beijing, Yang is considered as one of few “rising stars” in the Chinese contemporary arts scene. Using her expert skills in animation and video production acquired from the China Academy of Fine Arts BFA and MFA programs, Yang’s work is most well known for challenging traditional gender roles, specifically pertaining to Chinese women.

Approaching the installation, the massive projection hangs above a vintage Pac-Man-like video game arcade box. UterusMan is a highly engaging work that operates two-fold. While the video plays over head, the arcade box asks the viewer to participate with the piece and physically play the game created before you.

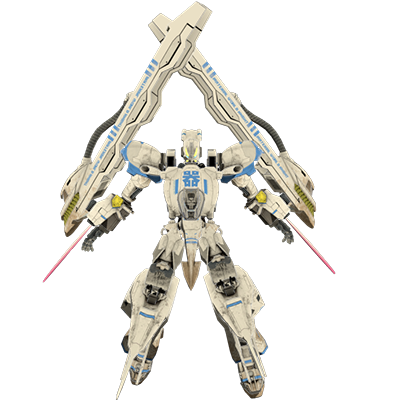

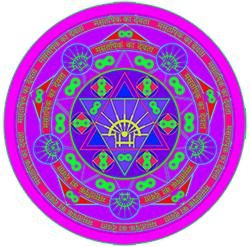

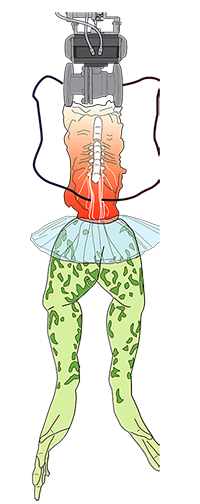

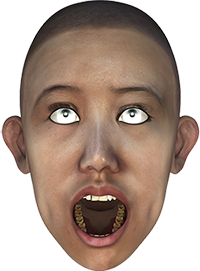

Inspired by a Japanese transgender artist in Tokyo, the work is a 3-D animation of a transgender character that soars through four different levels collecting coins in a Mario-Cart-like approach. Yang’s representation of identity is grounded in the physicality of her character. Although she labels the character as a “Man,” the presence of a female reproductive organ—where the Uterus actually functions as the character’s weapon in knocking through obstacles—is what makes this character trans.

While Yang maintains that the representation of the character is designed to question and challenge the traditional roles ascribed to Chinese women, this work clearly maintains a trans-representation that may prove problematic.

Yang engages feminist critiques (while also denying the label of a feminist in a NYT article), while simultaneously maintaining a progressive and non-binary point of view concerning body physicality and identity. While her character holds weight in terms of erasing bigoted notions traditionally attributed to the uterus– by animating and performing the uterus as a weapon– Yang ignores the transgender identity. This critique mostly has to do with the derogatory nature of the game’s title, UterusMan, where the character traditionally self-identifies as a trans woman.

Why then does Yang maintain the character’s trans identity when the name in itself has the potential to offend, or, further, demean, transitioning and what it means to be non-binary or a trans man or women.

Nonetheless, UterusMan is a part of Yang’s larger objective as a post-internet artist to live and operate almost entirely on the internet. Continuing to think about identity and self-expression, Yang deliberately seeks to disassociate from the label of a “Chinese contemporary artist,” explaining to the New York Times,

“By living on the Internet, you can abandon your identity, nationality, gender, even your existence as a human being. I rather like this feeling.”

Taken as a whole, however, the show’s diversity—in thought, content, form and medium—is indicative of the identities that the show aims to engender. Just as the diverse selection of works couldn’t be framed within a single definition or cultural category, the identities presented operate congruently, as the exhibition’s form follows function.

Lu Yang, UterusMan, screenshots