http://asiasociety.org/texas/interview-jin-shan-and-lu-yang

by NIKKI TRIPP

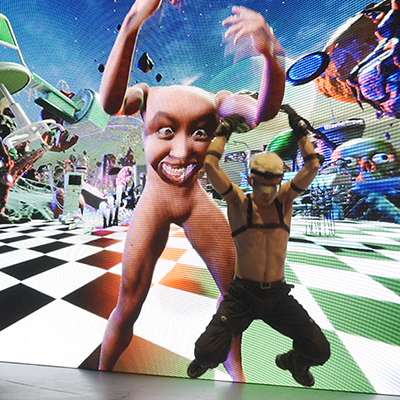

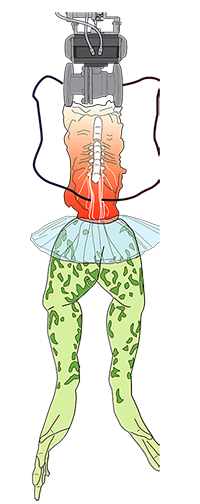

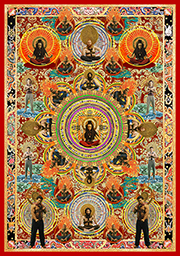

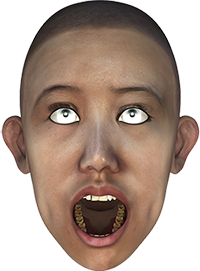

(Left) Jin Shan explains No Man City (detail), 2014, Tyvek on acrylic, aluminum frame, and LED projector, Tampa Museum of Art, Gift of the artist, 2013.004; (Right) Lu Yang, Courtesy of Beijing Commune

A consummate sculptor who has worked in a wide variety of mediums, Jin Shan often plays the bad boy with works that tweak viewers’ expectations. For example, earlier in his career he installed a life-size replica of himself, standing and peeing like a fountain into the Grand Canal for the 52nd Venice Biennale in 2007. With No Man City (2014) he takes a more reflective look at his relationship with his father, who is also an artist. Jin Shan’s utopian structure, stretching 25 feet wide, represents China’s future. Onto this element, he projects shadows of classical Chinese iconography — a crane, a sun, and a peony — all taken from his father’s more traditional paintings.

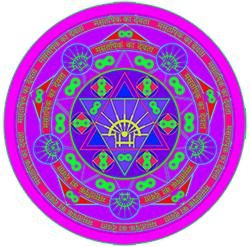

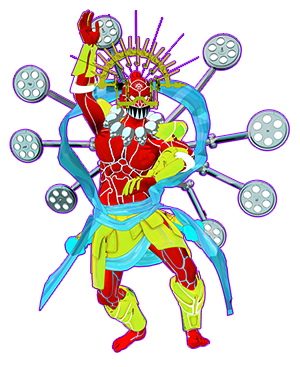

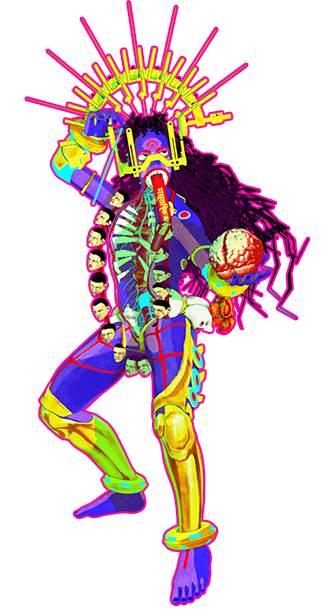

Considered a rising star in China, Lu Yang is an expert animator and digital artist who designs both installations and video projects. In 2014, she invented Uterus Man, inspired by a Japanese transgender artist in Tokyo. Other works such as Moving Gods and Delusional Mandala expand her engagement with religion and gender. Though Lu Yang, like most women artists in China, would not call herself a feminist, her works nonetheless challenge traditional roles ascribed to Chinese women.

Both artists’ works are featured in Asia Society Texas Center’s current exhibition We Chat: A Dialogue in Contemporary Chinese Art alongside 8 other artists. Jin Shan and Lu Yang spoke with Asia Society about the influences on their work, how the mediums they utilize affect the subject matter, and how Chinese contemporary art has changed in the past 20 years.

What are the main themes that you explore in your work?

JS: The main themes in my work involve a mix of humans, gods, power, and religious worship.

LY: My work mixes strategies taken from science, religion, psychology, neuroscience, medicine, games, pop culture, and music, and highlights the biological and material determinants of our condition. My work reminds us of our transient and fragile existence, but with an edge of dark humor that leaves no room for sentimentality.

What sparked your interest in this subject matter?

JS: My interest comes from my experience growing up under my father’s influence, along with the influence of contemporary Chinese thought. My father was a stage designer, and the massive scale and the special feeling of the stage helped me with my own creating. He represented a more traditional Chinese influence, but I always looked and thought like an outsider, so it was more like an opposite power that inspired me. If he went traditional, I would probably try contemporary, like the two faces of Gemini.

LY: Religion and science give us two totally different ways to discover the world. Our physical body discovers the world based on physical matter through science, while our upper mind finds the truth, maybe through some religious ideas.

How do you think the specific medium you choose to utilize affects the subject matter of your work?

JS: The medium I utilize is connected to the way I see this world. For my latest solo exhibition, I chose a fluid and hollow medium, because I doubt that the world is really as stable and solid as it looks.

LY: Like a package, the mediums of my works are the physical objects that spread my ideas to this world. I just choose the different materials to be the cover of my work.

In your opinion, what is different about the contemporary art we are seeing coming from China in 2016 (compared to 20 years ago)?

JS: By 2016, I think Chinese art has developed its market and has created more channels for artists to go through, but lacks some original motivation. 20 years ago, by contrast, almost no market or professional art space existed, so most artists created works only for their own enjoyment.

LY: I can only tell that artists who are my age are not very interested in political problems as much as artists from 20 years ago. Because we were born in this generation, our experience is different.

Your work challenges the viewer on a number of fronts. What is the most important for American audiences to understand?

LY: My work is open to all human beings, so I haven’t considered which country they’re from. The topic of my work is closer to boundless, so that everyone can understand.

What in your work addresses the generation gap between you and your parents’ generation?

JS: I can give many more opinions than my parents’ generation could. They just followed one voice which was decided by the character of the time.

Among your peers, is there any nostalgia for the past or is there a complete engagement with the present and future?

JS: Nostalgia grows with my increasing age. As I experience more in my life, I start to believe it is something in human nature. It happens to me occasionally, but there’s also inevitability inside of it.